how we actually evaluate agents (health)

29 Jan 2026In the last couple of months we’ve been working on a health agent. It was my role specifically to deal with the messy answer to the tough question: “is it good? worthwhile? valuable?”

I’ll try to describe here our attempt to answer this question. This follows Anthropic’s Demystifying evals for AI agents, which I recommend reading first if you haven’t.1 What I’m adding here is the specifics of applying these principles to health, what we actually learned when the rubber met the road, and where the general advice breaks down or needs adaptation.

Starting with tasks

First, probably a pretty important insight: we started by defining the specific tasks we would want the agent to be able to perform. We actually wrote early on that “Tasks is an abstraction that is meant to encapsulate a capability or to modularize a larger set of tools and context into something tangible that can be tested. The evals of each task is probably the main reason to have this abstraction.” I think this turned out to be right.

We tried to aim for tasks that are somewhat verifiable, and that include some element of orchestration or tool chaining. We defined different levels (easy, medium, hard) where the easy ones can probably already be accomplished with a pretty simple prompt and SOTA models today, and even the medium and hard ones can maybe be close given detailed enough prompting.2

We also noted some challenges ahead of time. In most examples people already have a deployed AI product generating traces. We didn’t have that, so generating evals beforehand was challenging.3 It’s somewhat circular with the task definitions, tools definitions and so on. We wrote at the time that “it’s also okay to start with vibe checks” - which I still think is true, though insufficient.

We tried both GPT SOTA models and OpenEvidence and looked at their responses to our queries. We found good things and bad things. Some failure modes we discovered there would later carry over to our own system (LLM-inherited, baked into the base model). Others would be specific to our scaffolding, our agent harness.4 This distinction ended up mattering less than I initially thought it would.

The metabolic health report as an “evaluation surface”

Because we wanted something more consistent and easier to develop against, we concatenated a bunch of those tasks into one thing you can call a “metabolic health report” (the reason it’s “metabolic” at this point is due to input modalities - CGM data, diet logging).

The goal was to: present the data itself, contextualize it with metrics and personalized insights, add actionable guidance, and connect the dots while grounding the claims. Importantly, the report had to be constructed of evaluatable tasks.

I think this was a clever bit. We could have separated it into specific prompts, and this would probably enable some different things. Arguably, this would create a more flexible system (I’m not sure our system right now would handle very well answering concrete, limited in scope questions). But the report gave us a controlled evaluation surface - same input, same task, observable improvement over time.5

The hierarchy: what we actually solved

We mostly solved the general structure of it, the hierarchy. Like, we know that similarly to SWE, we have the equivalent of a unit test, we have the equivalent of an integration test, and thankfully because in many senses the entire task itself was at the early POC stage rather well defined, we also have the equivalent of an end to end test.

But here’s where it gets interesting. There’s this tension between form and essence.6 We can check form pretty well: Did the citation exist? Was the tool called? Do the numbers in the output trace back to tool outputs?

The Anthropic post talks about two types of evals: capability evals (what can this agent do well? - should start at a low pass rate, giving teams a hill to climb) and regression evals (does the agent still handle all the tasks it used to? - should have nearly 100% pass rate). Looking back, I think we focused mainly on regression-style thinking: see a failure, make sure it doesn’t happen again. But the pattern of “see them fail and then add a skill or change something to make them green” - maybe that is the same pattern of hill-climbing, or at least similar.

Error analysis: it starts with the data

Before we could add evals, we had to understand what was actually failing. This meant doing what everyone says you should do but few actually enjoy: manually going over the data. It has been repeatedly stated in the past how valuable this is. Our case wasn’t any different - it’s extremely valuable.

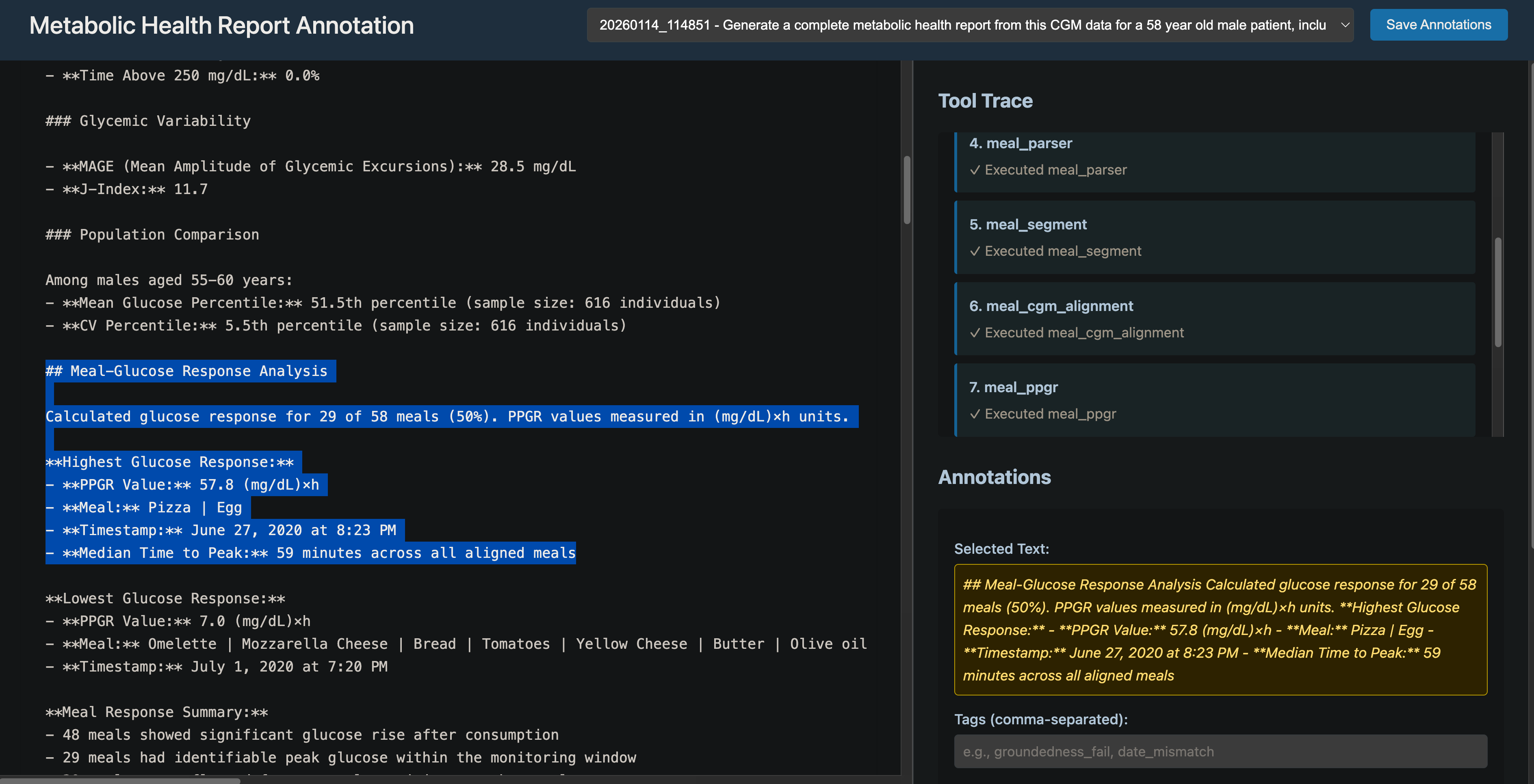

I built a simple annotation tool - maybe a day’s work, completely ad hoc, knowing it would be useful for this POC stage and being perfectly okay with not needing it later. Just the ability to properly show markdown and the tool chain beside it, and a small place to highlight quotes and write annotations. That was really nice and really useful. The ratio was great - minimal investment, high return.

The annotation tool: markdown output on the left, tool trace on the right, annotation panel below. Ad hoc but useful.

The annotation tool: markdown output on the left, tool trace on the right, annotation panel below. Ad hoc but useful.

We did detailed error analysis comparing against our GPT baseline.7 Here are the major failure points we discovered:

Ungrounded percentiles/comparisons. Population percentiles appearing without cohort size disclosure or traceable tool output. “Digital twin” comparisons fabricated without reference dataset.

Diagnostic language misuse. Terms like “CRITICAL,” “SEVERE HYPOGLYCEMIA,” “IMMEDIATE ATTENTION” applied to likely CGM artifacts in healthy individuals. Diabetes guidelines (54 mg/dL thresholds) misapplied to non-diabetic physiology.

Missing modality blindness. Post-meal and exercise claims made without diet/activity data. The agent sometimes fails to caveat when required data is unavailable.

Pseudo-evidence citations. Claims labeled “evidence-based” without guideline citations. ADA/ATTD mentioned but specific criteria not actually applied.

Over-interpretation from CGM alone. Physiology inferred (“insulin sensitivity,” “reactive hypoglycemia”) from metrics that don’t support such conclusions.

We stated our goal simply: address as many of those as we can. The pattern became: see a failure, add an eval that catches it, add a skill or change something to make it green, move on. Small circuits of failure → eval → prevention. Whether the root cause was LLM-inherited or scaffolding-introduced mattered less than whether we could catch it and prevent recurrence.

What we couldn’t easily measure: the essence problem

Even if we solve the foundational issues (and we did make progress), gaps remain. This is directly linked to what I call the essence problem. We can check form. But it’s still hard to evaluate:

Clinical appropriateness. When the system thinks findings are real but the person is healthy. When it applies the wrong clinical frame.

Narrative coherence. Does the report tell a story, or is it a collection of metrics?

Utility. The hardest one, maybe. Trying to answer the question “is this helpful” - to the participant, to the clinician.

Some meta point to consider: maybe some essence evals would require us accepting fuzzier metrics or human judgment. Better to measure imperfectly than to ignore entirely.

The thing that lives in my head

There’s a finding from Google’s work on health agents (The Anatomy of a Health Agent) that constantly lives in my head. When presented with different answers with differing degrees of “professionalism,” ordinary users are not so good at sorting through and correctly recognizing which output is better. Concretely, given two health reports - one well-established and would gain approval from experts, and the other AI slop - many people won’t be so good at figuring out which is which. Meanwhile, experts can easily tell the two apart, with a high degree of inter-observer reliability.

To be frank I’m not sure it’s directly related to the evals piece, but it just so constantly lives in my head that it’s hard to avoid when thinking about this work.

I think it hints at something deeper. What is it actually hinting about? From my point of view, the Google paper showed that even though the more complicated architecture prevailed on metrics, on evals, on benchmarks, and even on expert opinion - it didn’t matter to the end user. There’s a tension here. You do want a system that is better all around. Better on evals, better on benchmarks, better according to experts. This is the thing you want to expose and bring to general availability.

But then you’re doing something that in some sense ignores the users.

My answer, at least for health: in terms of integrity, you still have to choose the system that provides better answers. You can’t ship something that is slop. Hopefully over time it gains trust because it actually works - because when someone follows its guidance, things go well.

The agency question

There’s a tough question I kept in the back of my mind: did we end up over-complicating something that had the potential of being pretty simple by trying to force it to become an “agent”? Where agency wasn’t needed most if not all of the time?

The metabolic health report, as an evaluation task, could arguably be a workflow with simple rule-based conditions. You could make that case.

We defined a diverse set of tasks with the input modalities we decided to include - diet logging and continuous glucose monitoring data. We were actually trying to build a system that would be the basis of something with a bit more agency, being able to answer a diverse set of tasks. The metabolic health report was our version of being able to run the same prompt with the same system and see improvement in our results.

Recently we encountered a Washington Post piece about failure modes in GPT for health advice.8 Almost as a challenge, we wanted to see how our agentic system would handle the same kind of task - cardiovascular risk assessment. We added a skill, tried with roughly the same prompt structure, and it worked. It didn’t hallucinate the way the article described. The architecture we built - the task abstractions, the eval framework, the tool integration patterns - transferred. We didn’t rebuild from scratch. The fact that we created a system with those hill-climbing evals we described earlier, it kind of proved itself(!!). Given this experience, I think the agent architecture was forward-looking infrastructure that hadn’t been fully tested yet. Now it has been, a little more.

What we contributed, what we learned

You know, in some sense the question really to answer is “what did we contribute to the world?” and “what did we learn in the process?” These are the things I should be focusing on.

What we learned is probably clearer: the form/essence gap is real and doesn’t go away. Small circuits of failure → eval → prevention work. Error analysis is worth the time. Expert opinion is non-negotiable. And the task abstraction - defining what you want the agent to do before building it - pays off.

What we contributed is maybe just a specific case study of what Anthropic and others have talked about in the abstract. We implemented the lessons. We discovered which parts of the general advice break down when you’re actually in a health domain, looking at CGM data, trying to figure out if “reactive hypoglycemia” is a reasonable inference or a hallucination.

Maybe that’s enough. Implementing lessons is good. Showing what actually happens when theory meets practice is useful.

What I’d tell someone starting this

If you came to me tomorrow starting a health agent project and asked how to approach evals:

This is going to be harder than you think. Even if you follow a thorough process of error analysis, it’s hard to do without user feedback. It’s hard to do without expert opinion. Expert opinion is something you must have.

Small circuits work. See a failure mode, create an eval that finds it, fix it, prevent recurrence. Don’t overthink the taxonomy of why things fail. Just catch them and stop them from happening again.

Invest a little in tooling for yourself - an annotation interface, a way to see traces alongside outputs. It doesn’t have to be fancy. A day of work paid off in weeks of usable error analysis.

Accept that some things you care about - utility, clinical appropriateness, narrative coherence - won’t have clean automated evals. That’s okay. Measure what you can. Use expert judgment for the rest.

And define your tasks before you build. “The evals of each task is probably the main reason to have this abstraction.” We wrote that early. It turned out to be true.

(hopefully) this will be a part of a series exploring different aspects of our health agent work. The goal is to answer two questions: what did we contribute, and what did we learn?

-

Anthropic aren’t the only ones writing about this - OpenAI recently posted about evaluating skills specifically, which is a nice complement: Eval Skills. And Hamel Husain’s work on evals is great. ↩

-

And trial and error, and health data. Ok, maybe just the medium ones. The hard ones were genuinely hard. ↩

-

This is a chicken-and-egg problem: you want decent performance before deploying to users, but some of the most important evaluation signals (especially around “essence” - utility, clinical appropriateness) require actual user feedback to assess properly. ↩

-

The Anthropic post defines an “agent harness” (or scaffold) as the system that enables a model to act as an agent - it processes inputs, orchestrates tool calls, and returns results. When we evaluate “an agent,” we’re evaluating the harness and the model working together. ↩

-

There’s an idea we ended up not exploring: the concept of “agent state” as a middle ground where we could run some evals (mostly against ground truth). We did use the traces quite a lot, which was useful. What we actually did was a “right shift” instead of “left shift” - we shifted everything to evaluate the end result of the metabolic health report rather than intermediate states. For a POC this was fine, but I still think agent state as an evaluation surface might be worth exploring in the future. ↩

-

Coming from a background in NMR spectroscopy and signal processing, this was disorienting. In spectroscopy, ground truth is relatively clear - the peaks are the peaks. In this domain, the ground truth you actually care about is expensive, fuzzy, or sometimes unknowable. ↩

-

I had a dual role here - looking at outputs both as a physician (is this clinically appropriate?) and as a research scientist (do these numbers trace back to tool outputs?). Some things are flat out wrong and easy to catch. But some things are not such giveaways - even if the numbers are accurate, the context might be misleading. Having both perspectives was useful. ↩

-

The Washington Post article. The general pattern was GPT providing cardiovascular risk assessments that included hallucinated numbers and misapplied clinical guidelines - exactly the failure modes we’d identified and built evals against. ↩